I’d always considered my wife’s home village to be “rural” because there aren’t many people in it, the police station is only open on Tuesday, and I can walk the length of it in under six minutes. By virtue of having been there several times and having attended town gatherings and New Year’s Eve parties I can say that I’ve likely met or crossed paths with every single person there who isn’t holed up in their domicile.

So, when my wife’s family told me we were going to a wedding “in the middle of nowhere” it tested the limits of my imagination. We’re five hours from any major city. Two hours from a small city. We’re 35 kilometers from a large town. There are ostriches running around. Aside from a trek to the mid-Atlantic, I had a hard time imagining we could get more rural.

“You’ll see,” they said.

There were no hotels where we were going so we’d be staying at the bride’s farm house, I was told. And though I’ve been to weddings for Tomek & Ania, Gocha & Fabian, Tomek & Ola, Maciek & Aga, Piotr & Monika and my own, I was told that this particular Polish wedding would be “different.”

I was intrigued.

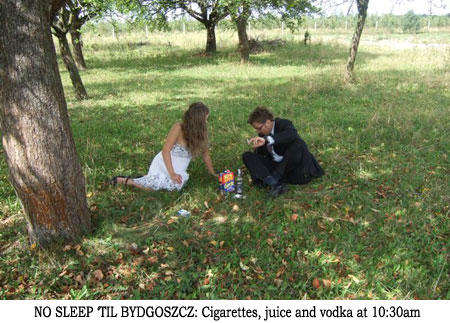

So, in the wee hours of Saturday morning we hopped in a hired van and drove. And drove. And drove. We drove for six and a half hours. The terrain changed from pine forests and wheat fields to apple trees. Because of all the apple trees I assumed we were in Apple Country. This was later confirmed by my brother-in-law.

“This area is known for their apples,” he said.

The paved road ended, turning into a black dirt road that we followed until it became a tan dirt road. No one was exactly sure where we were going, as the house was described as being near somewhere. Eventually we sighted a mother and young girl stringing up some balloons: we’d found the party farm. The driveway was half a kilometer long, running through recently harvested fields of wheat. It brought us into a courtyard with farm buildings in various stages of disrepair. There were free-range chickens, turkeys, pigeons, cats and dogs. A calf on a short tether mooed to a cow hidden behind a wall. Roosters meandered about, crowing, even though it was mid-afternoon. I’d always believed they only cock-a-doodled in the morning. I was apparently wrong. The pigeons sat atop a coop I’d mistaken for an outhouse and cooed.

An older man, father of the bride, appeared and greeted everyone. He fetched his wife who in short order had set up a table outdoors and was serving us coffee, cakes and home-made sausages. I declined the sausages citing the fact that I was sitting in view of a cow that might actually be related to them. Plus there were flies everywhere, on account of the whole place smelling like manure.

Amidst all the rustic beauty, a lady leered at us.

The lady looked like Bette Davis, but crazier. She stood wide-eyed and silent, fixating on one or two folks before shuffling off to take a new position and acquire new targets. She was like a ninja, a crazy ninja, appearing and disappearing as if by magic. We later came to learn that the death of her mother many years ago had thrown her over the edge. She’d mostly stopped talking after that and had taken to wandering around and unintentionally frightening people. “Don’t make eye contact,” I was told, “And if she hits you, don’t be surprised. She hits people if she decides she doesn’t like them.”

I’d been there all of ten minutes and I was afraid.

The brother of the bride appeared and I went to shake his hand. He surprised me with a shriveled right arm. I later came to learn he was very much in love with my wife, despite being related to her, and had plans to steal her away from me later in the evening when I would presumably be distracted by vodka. I admire his tenacity and strength, as far as not letting a physical handicap get in the way of his self esteem, but I question his ethical judgment in trying to woo his married, twice-childed cousin.

We sat outside and drank our coffee next to the dilapidated remains of the original farm homestead. It was over a hundred years old but had been abandoned since the new farmhouse was built behind it. It was slowly being dismembered and burned. Father of the bride gave us a quick tour. “Five of us slept here,” he said – standing in a room the size of an office cubicle. I made a mental note to never again complain about New York apartments. Everything was covered in chicken poop or cobwebs, but you could make out a very intricate pattern on the walls – a paint job that must have taken ages to do in the days before Home Depot and Do-It-Yourself stencil kits. It seemed a shame to let it all go to pot, but until they finished burning it piece by piece the old house was only used to store the family’s main source of income: red peppers. Judging from the scattered feed, feathers and poop, chickens hid out here when it got cold.

The new house was less aesthetically charming, but much nicer. No cobwebs. No poop. Unbroken windows. It was completely square in the minimalist Soviet style. There was one bathroom. The bathtub had a hot water heater hanging over it. The hot water heater was electric as evidenced by the cord that dangled precariously across the tub and plugged into the power outlet above the tub that any decent building inspector would have demanded be removed.

Wedding guests began to arrive, and slowly the house and courtyard began to fill with family and friends – many of whom needed to get clean and dressed after their long drives. A queue for the bathroom soon formed and in no time the dangerous hot water heater was unable to keep up with demand. Rather than stand in line so I could squat in a worn tub and drizzle freezing water on myself I opted for a military shower: a rubdown with baby wipes. It was quick, they were room temperature, and they had the added benefit of making me smell like an adorable baby’s bottom.

At the appropriate time we all headed for the church. It’s Polish tradition to block the path of the bride and groom with whatever it takes to block the path: rope, bicycles, children, bulldozer, fire engine – I’ve seen it all. The procession stops, the bride and groom get out of the car, you offer congratulations and then they give you a bottle of vodka (or candies, for kids) and you get out of the way. This is a sweet tradition but it makes going anywhere take twelve times as long – especially if the whole village has heard about your wedding.

The church we finally arrived at was an inexplicably large entity considering we were not near any conceivable population center. It seemed akin to building a Wal-Mart in Antarctica. The cathedral’s simple exterior belied its absolutely gorgeous interior. The pulpit was one of the most beautiful I’ve ever seen – designed to look like the bow of a ship, despite the fact the Baltic is 500 miles away.

Every aspect of the wedding service was captured by the videographer who expertly stood between the audience and the action. He blocked the view of the signing of the wedding contract, blocked the view of the couple exchanging rings, blocked the view of the couple taking communion. The service he dutifully blocked was interrupted by a momentary loss of power, but the organist recovered nicely. The videographer continued to stand in the way and in due course the couple exchanged their vows behind him and then headed to the reception – my favorite part of any wedding.

Polish weddings are two or three day affairs, depending. Close friends and relatives often have a Friday night “glass breaking” party, so-named because glass gets broken. The wedding ceremony is on Saturday and then the party officially starts. It lets up Sunday morning when folks take a nap, but it resumes Sunday afternoon. By Sunday evening folks are on their way home – often dreadfully fatigued and poisoned by alcohol.

At the reception hall guests enjoy a glass of sparkling wine (can’t call it Champagne, because Russians made it) before the doors open and everyone starts jockeying for their seats. Every table has a selection of cakes, meats, breads, fish, cheese and fruits. Hot soup is served. Amidst the slurping, bottles of vodka are placed on the tables. Shot glasses are filled and eventually a boisterous toast is made to the bride and groom. The party starts and the musicians fire up the band. The band, in this case, had planted themselves right next to me. I had a saxophone in my ear for a good twenty minutes before they saw fit to wander elsewhere.

The bride and groom sat underneath an electric Virgin Mary that pulsated colors. In all my Polish weddings it was the first time I noticed any religious symbols at the actual reception. The new couple drank from shot glasses that were symbolically tied together with a string.

The crowd ran the gamut from young to old. One by one I found myself being introduced to them. A short, cheerful, red-faced man led me to a small keg that rested on a table of cured meats, pâté and pig tails. It was his treasured moonshine – homemade vodka – and I was being invited or possibly ordered to have some. It tasted like really good tequila, and evaporated on my tongue as it was pure alcohol. When I told him I liked it he immediately filled my glass again, without asking. Aware that I’d be on all fours in minutes at that rate, I excused myself to use the bathroom where one roll of paper towels had been supplied for all 220 guests.

All Polish weddings have bands and they all tend to play the same songs. There’s a lot of dancing and after a few numbers the band inevitably sings a little ditty which translates to “And now we go for another vodka” at which point everyone leaves the dance floor and heads to their respective shot glass.

This band was a little different though. Los Diablos Emeritos played the classics, sure, but this was the hinterlands and they weren’t afraid to be a wee bit bawdy. Even with the many kids in the audience. Every so often a word would capture my attention, causing me to ask for a full translation.

“Did he just sing old woman and ass?” I’d ask.

“Yes. The old woman has a cork in her ass.”

At midnight it was officially my wife’s birthday – a fact that did not go unnoticed by lead singer Robek. He singled her out with an interactive song about what kind of man she preferred. The correct answer, in defiance of the fact her American husband was sitting there, was “Polish.” The song was about as politically incorrect as one can get. After Robek sang lyrics like “Would you like an Asian man, with his tiny little pee-pee?” he’d thrust the microphone in her face and wait for the obligatory “No!” which would then propel him to the next cringe-worthy verse. It was a no-holds-barred juggernaut of country comedy that had at pretty much everyone: Russians, blacks, French, Arabs, English. Oddly, and for the first time ever, no one was picking on the Americans.

As an American in the Polish outback who spoke vaguely understandable Polish – especially when lubricated – I was more of a novelty than usual. People wanted to say hello and have a drink with me. And, of course, it’s rude to decline. When Barbra from Ukraine wraps her arm around you and demands you drink with her, you drink with her. And when she comes back three minutes later to do it all over again, you do it all over again. This presented a problem.

There were 220 guests. If even a fraction of them wanted to do a shot of vodka with me, I would be dead in very little time. In order to survive, I began pouring water in my shot glass – an egregious violation of Polish drinking protocol, mind you, but I was willing to risk being shamed in order to preserve some level of consciousness. I am simply not in the same drinking league, nor would I want to be. This kind of lifestyle – hard drinking, heavy smoking, pepper farming – takes its toll on your body. People I thought were 60 were 40. They live a tough, strenuous life. On the other hand, they really seem to be enjoying it. In comparison American weddings seem half-hearted and boring – everyone bitching about the line at the open bar while trying to determine what hors d’oeuvres they’re allergic to.

My sneaky water shots kept me alive and impressed Barbra from Ukraine – who I strongly believe could out-drink a small garrison of Romans.

I began to fade at 4am, though I clearly was in the minority. Sadly, I’d been outlasted by countless grandmothers and grandfathers, Barbra from Ukraine, and men half my size who’d been up at dawn the day before slaughtering pigs. But I was done. I crawled into the van and was back at the farm house by 5 – just in time for the roosters and cows to start up. The party made its way back to the farmhouse and raged until 11am Sunday, at which point folks broke for a little nap.

After folks had a handful of hours of rest the party resumed. Attire was casual – a good thing, as my suit was in a pile on the floor. Back at the reception hall folks sat back down at the tables and prepared, amazingly, to drink again. Yesterday’s leftovers were served, and new bottles of cold vodka placed on every table. It was mere moments before someone was holding their shot glass up and waiting for me to do the same. I sheepishly declined – I’d slept long and well compared to everyone else and actually felt really good. I didn’t want to ruin it.

I rejected numerous offers to add more vodka to my system, eventually procuring a can of beer as a prop. It made it easier to turn down vodka shots when I pointed to it. “Not right now,” I’d say, “I’m having a beer.”

Eventually I had a few cans of beer. Inhibitions fell to the wayside. From there it was a slippery slope. Soon I found myself accepting vodka shots in the interest of international friendship. As I stood in the men’s room – which had run out of its one roll of paper towels the previous day – I looked in the mirror and saw a fatigued, red-eyed man staring back. Then it occurred to me: These people are trying to kill me.

Nevertheless, as night fell I wasn’t in as bad shape as many of the others. Certainly in no position to operate heavy farm machinery but a far cry from those folks whose bodies had simply turned off. I meandered about, striking up conversations with people who confused me.

“We live in New York,” I said in response to one man’s question.

“Oh. My wife died sixteen years ago,” he said.

At 8:30pm on Sunday the party was officially over. A drunk pepper farmer offered me an overly energetic goodbye five times until I finally broke free. Barbra from Ukraine gave me a warm hug and slurred niceties. The distant cousin with the withered arm – who’d apparently spent the morning trying to seduce my wife as I slept – said it was nice to have met me. We wished the bride and groom well then clambered back into the van for the trip home. As we pulled onto the road my brothers-in-law began to sing boisterously, but fears they were going to bellow for the entire trip dissipated twenty seconds later when they simultaneously passed out. Only then did I realize the folly of my ways. Everyone else, exhausted and drunk, would be sleeping the six-hour ride home. I was a well-rested teetotaler by comparison and would subsequently be forced to stare into the dark abyss of the Polish countryside at night, left to contemplate the crime of having lead Barbra from Ukraine to believe I could keep up with her.

Great story! That Barbara is too funny.

I always thank the gods that my wife and I didn’t have a really traditional Polish wedding. It was more like: Polish wedding lite.

Our reception did manage to last into the wee hours of the morning but at that point it was basically over. Inexplicably enough, though, my father who rarely drinks thought it would be highly amusing to drink straight from the Luksusowa bottle at 11am after a few hours of sleep. Polish weddings are quite liberating somehow.

Oh and the water/vodka thing: Everyone does that. Usually the groom’s best man gets him a “special” bottle of vodka for when people want to do toasts. Unfortunately there were so many toasts at my wedding that we went through the special bottle too fast and got pretty drunk anyway.

One of the only times I ever recall seeing my Polish grandmother look surprised was when my sister made her a drink of vodka and iced tea. It had never before occurred to my grandmother to actually MIX vodka with anything other than ice.

Very funny Brian :)

And that ninja… I wouldn’t find better word! I hope she doesn’t read “banterist”… Bye!

Is this a typo?? No! It can’t be!

“… many of whom needed to get clan and dressed after their long drives…”

Great story.

[ Nuts. Happens to the borscht of us. ]

That is a dead on description of a Polish country wedding.

It’s been 15 years since I have been. At that time, I had just graduated from university. I remember drinking lots of vodka and beer. Man it was a good time.

It’s definitely time to go back.

Sto Lat!

Love love love this story! I laughed until I cried, and then I laughed until my belly hurt, and then I laughed until I woke my boyfriend up. (p.s. Pls fix typo in “Polish forces volley … ” caption. K Thx Bye.)